Stephanie Jones: Book Review - Stolen Lives by Netta England

- Publish Date

- Friday, 29 August 2014, 12:00AM

- Author

- By Stephanie Jones

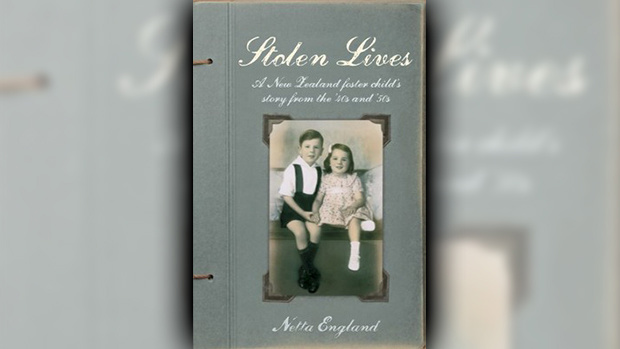

When Netta England got married in the late 1950s and took her husband’s name, it was her fourth surname. She was 21 years old. Her self-published memoir Stolen Lives, in which she recalls her experiences as a foster child in mid-century New Zealand, is a story of terror, lack and loss stemming from inconceivably poor decision-making by agents of the Department of Child Welfare, the government body responsible for the care of England, her older brother Ray and thousands of other children like them.

Why so many people failed so miserably time and again is a matter for social historians, but England astutely observes that the single, middle-aged status of every welfare agent with whom she was directly involved from the age of six months, when she was permanently removed from her birth mother’s care, cannot have been sufficient qualification for the challenging task of placing vulnerable children in new homes.

In using her story as an example England lays bare the fallible system of state-managed care of children as it was conducted for many decades in foster homes and government-run institutions. That England and her brother were placed in the care of a man with a gambling problem and inability to maintain paid employment and a mentally and physically ill woman who was later diagnosed with a severe personality disorder; that the placement went ahead despite the woman’s insistence that she didn’t want the girl child, only the boy; that repeated entreaties from blood relatives to care for and raise the children were ignored.

England’s own pleas for help to the “Welfare ladies” fell on deaf ears, and when, decades later, England reviews the records of those conversations in her file, she finds they differ greatly from her own recollections. That she obtained the file at all was a small miracle; on first pursuing information about her case in 1979, she was told by officials that all records had been destroyed a decade earlier. A lawyer’s request in 2004 uncovered the lie, and delivered the material to her in its entirety.

It would be understandable if England were overwhelmed by bitterness and rancor, but through a combination of luck, perseverance, strength of character and a touch of cognitive behavioural therapy – she references a book that helped her change her thought patterns in mid-life – she has enjoyed what many would regard as an enviable adult life.

She doesn’t shy away, however, from apportioning blame where she believes it’s due. England’s tale verifies her title, proving that the two children’s lives were stolen by a cadre of government representatives whose behaviour exceeded gross incompetence and approached outright malfeasance.

That England is not a writer by trade is evidenced by the occasionally disjointed structure and the stilted nature of the recounted conversations, many of which took place decades ago. But the flaws within Stolen Lives fade into insignificance next to the sincerity of her story and the earnestness of its expression.

The most troubling aspect of her story, and that of her doomed brother Ray, is its predictability. New Zealand has set a perverse international standard for child abuse and neglect, and even as we battle for improvement the effects of trauma are felt by those now well into their dotage. Some relief may come from the New Zealand branch of CLAN (Care Leavers Australia Network), a charitable trust and support group set up by England for former wards of the state. Meanwhile, Stolen Lives contains the echoes of many unremembered voices.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you