Stephanie Jones: Book Review - Wildlight by Robyn Mundy

- Publish Date

- Wednesday, 18 May 2016, 2:17PM

- Author

- By Stephanie Jones

Nature is the star of Wildlight, the evocative new novel by Robyn Mundy, in whose hands the earth and ocean and their respective creatures are celebrated and described with reverent attention. Most of the story takes place on Maatsuyker Island, home to Australia’s southernmost light station, where Mundy has lived and worked.

The plot centres on 16-year-old Stephanie West, who travels to the island with her parents to spend several months in a house “as skanky as a Kings Cross backpackers” and record weather readings three times daily. These are transmitted electronically to Hobart, though to the vocal dismay of Stephanie, who harbours a teenage girl’s preoccupations and anxieties, there is no cellphone reception on the island.

An amalgam of history and circumstance has drawn the family to Maatsuyker, where Stephanie’s mother, Gretchen, spent part of her girlhood with her light keeper father. Stephanie’s father is suffering from a health condition that threatens to end his career in radio, and the trio are enduring a bereavement that is rarely discussed – the death, two years before, of Stephanie’s twin brother, Callam.

His spectre looms mutely in their lives and wends through the text, which Mundy wisely declines to fill with explanation or remonstration. There is no one to be blamed and no satisfying answer to be found, as is often the case in a young person’s death. The absence of Callam lends a heavy undertow to the tension between mother and daughter and more weight to the burgeoning, beautifully rendered relationship between Stephanie and a local fisherman, Tom Forrest.

Nineteen-year-old Tom is in reluctant thrall to his brother, Frank, who operates his crayfishing business well outside local ethics and treats his younger sibling as chattel. Anyone meeting the pair is quick to observe Tom’s vulnerability and the unhealthy dynamic – like “a continent buckling, a tectonic rift” – between the brothers. Tom, who has never travelled further than Melbourne, is conscious of the socioeconomic divide between himself and Stephanie, whose life in Sydney includes a tony high school, ski trips and overseas travel.

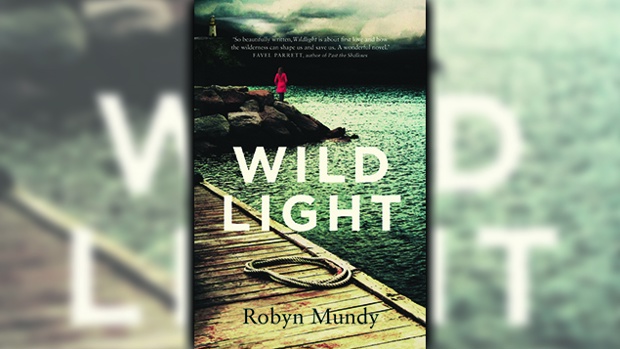

Though Mundy’s storyline weaves and darts with energy and no small amount of suspense, as unfinished business is addressed by an adult Stephanie in the present day, Wildlight’s chief attraction, hinted at by the gloomy loveliness of the cover art, is the portrayal of the environment of Maatsuyker Island, referred to by locals simply as ‘Maat’ (‘Mat’).

Mundy’s prose is redolent with the sights, sounds and scents of sea and sky: clusters of mutton-birds return to nest, the air filling with the rancid smell of their oil; fisherman risk their lives to bring in their catch in violent weather. The island is not a safe or easy place, and every day is a workday. Maat’s hostility to human comfort doesn’t dilute its beauty or allure; as Stephanie reflects on her departure, “The island looked slender, velvet folds of green draped across its spine.”

At times, the ceaseless glorification of nature has the tone of a more pensive David Attenborough narration, but this is no bad thing. Mundy honours the traditions of light keeping, a practice founded on numberless years of hard physical work and diligence, and dependent on the support of a tight-knit, functional community.

Above all, she acknowledges vagary, the element of chance that plays its hand in every existence: “Perhaps we navigate life that way. Perhaps we change course at precisely the wrong moment, blink and miss landfall.” Wildlight beckons to a reader seeking entry to a different world.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you